When you think about life-saving medicines, you probably imagine pills in a bottle or injections in a clinic. But behind every dose of antibiotics, antivirals, or blood pressure drugs in a low-income country, there’s a quiet but powerful force: the WHO Model Formulary. It’s not a list you find on a pharmacy shelf. It’s a global rulebook - one that decides which medicines should be available to everyone, no matter where they live.

What the WHO Model Formulary Actually Is

The World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) is often called a formulary, but it’s not like the ones in U.S. hospitals or insurance plans. It doesn’t tell doctors which drug to prescribe based on cost-sharing tiers or pharmacy networks. Instead, it answers one simple question: Which medicines are so vital to public health that every country should make sure they’re available?

First published in 1977, the list has been updated every two years. The latest version came out in July 2023 - the 23rd edition. It includes 591 medicines covering 369 diseases. Half of them are generics. That’s not an accident. The WHO doesn’t just accept generics; it actively pushes for them because they’re the only way to make life-saving drugs affordable at scale.

Here’s how it works: every medicine on the list has to pass a strict test. It must be proven safe and effective through high-quality clinical trials. It must work better than or at least as well as alternatives. And crucially, it must offer real value for money. The WHO uses a metric called cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). If a drug costs more than three times a country’s GDP per person, it usually doesn’t make the cut - unless it’s for a deadly disease with no other options.

Why Generics Are the Heart of the List

Generics make up 46% of the entire WHO Model List. That’s 273 medicines. Why so many? Because brand-name drugs are often out of reach for the poorest countries. A single course of HIV treatment used to cost over $1,000 a year. Today, thanks to generic versions approved under WHO standards, it’s under $120. That drop - 89% - didn’t happen by accident. It was driven by the WHO’s insistence on quality generics.

The WHO doesn’t just say “use generics.” It demands proof. Every generic medicine on the list must meet WHO Prequalification standards. That means it’s been tested to match the original drug in how it’s absorbed by the body. For most drugs, the generic must deliver 80-125% of the active ingredient compared to the brand. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows - like warfarin or epilepsy meds - the range tightens to 90-111%. These aren’t suggestions. They’re requirements.

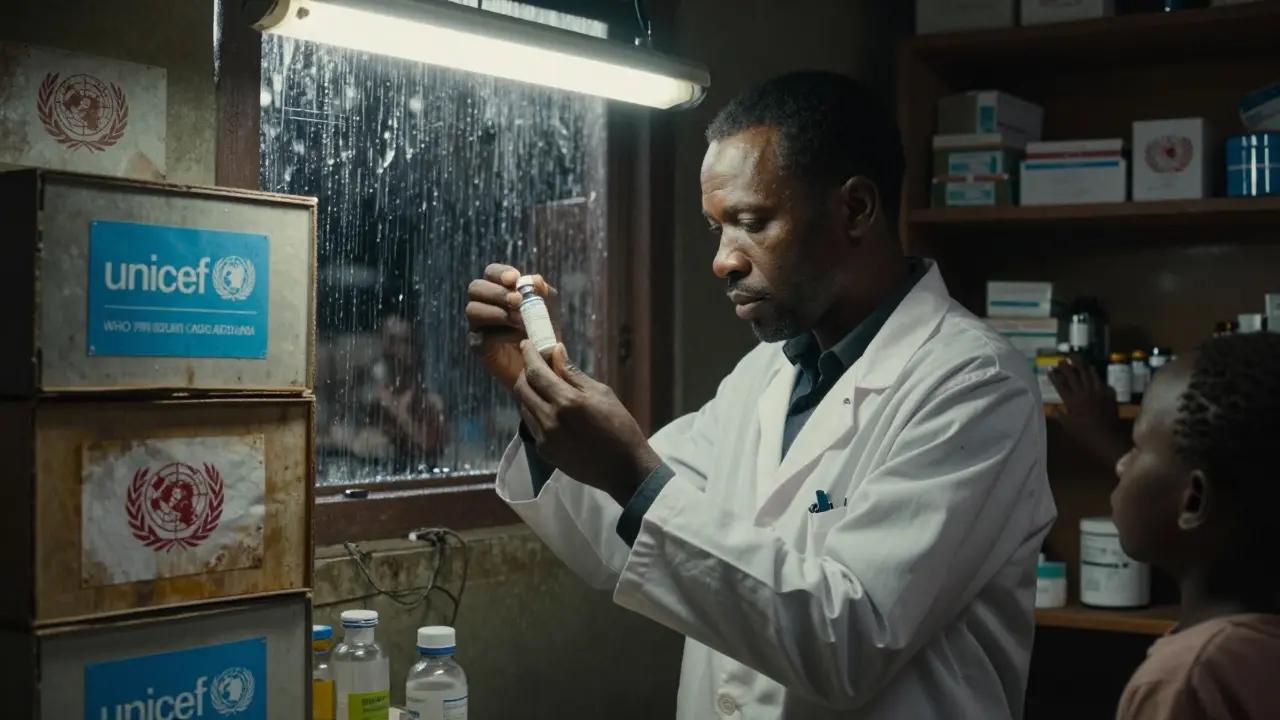

Over 92% of the generics on the list have passed this test. And because countries trust the WHO’s stamp, they can buy these medicines in bulk through UN agencies like the Global Fund or UNICEF. In 2023, about $15.8 billion in global medicine purchases followed the WHO list. That’s billions of doses reaching people who would otherwise go without.

How Countries Use the List - And Why It’s Not Always Easy

More than 150 countries have created their own national essential medicines lists, mostly based on the WHO model. In Ghana, adopting the list led to a 29% drop in out-of-pocket spending on medicines between 2018 and 2022. In India, hospitals cut antimicrobial costs by 35% after switching to WHO-recommended generic antibiotics.

But here’s the hard truth: having the list doesn’t mean having the medicine. A 2022 survey of 1,250 health facilities in Nigeria found that only 41% of the medicines on their national list were consistently in stock. On average, each essential drug was out for 58 days a year. The problem wasn’t the list. It was broken supply chains, underfunded logistics, and poor storage.

Even when medicines are available, quality is a gamble. WHO surveillance found that 10.5% of essential medicine samples in low- and middle-income countries were substandard or fake - especially antibiotics and antimalarials. That’s not because the WHO list is flawed. It’s because enforcement at the local level is weak. A medicine can be WHO-prequalified in India, but if it’s repackaged and sold without oversight in a rural clinic, all bets are off.

What the List Doesn’t Do - And Why That Matters

The WHO Model List doesn’t tell you how to pay for medicines. It doesn’t create insurance tiers. It doesn’t rank drugs by profit margins. It doesn’t include every new drug just because it’s flashy. In fact, only 12% of new medicines approved between 2018 and 2022 made it onto the 2023 list. Compare that to U.S. formularies, where nearly 40% of new drugs are added. The WHO waits for proof of real-world impact, not just clinical trial results.

It also doesn’t give detailed dosing instructions for kids or elderly patients in every context. A 2022 survey of health workers in 47 low-income countries found that 68% said the list lacked enough guidance for pediatric use. A child’s dose isn’t just a smaller pill - it needs the right formulation, taste, stability, and safety data. The WHO has improved this. In 2023, 42% of listed medicines had age-appropriate formulations, up from 29% in 2019. But there’s still work to do.

The Bigger Picture: Global Equity in Medicine Access

When you look at the numbers, the WHO Model Formulary isn’t just a list - it’s a tool for justice. Countries that follow it spend 23-37% less on medicines while achieving better health outcomes. The median price of generic HIV drugs has fallen by 89% since 2008. Treatment coverage has jumped from 800,000 people in 2003 to nearly 30 million today.

But the system has cracks. Seventy-eight percent of generic production happens in just three countries: India, China, and the U.S. That made supply chains brittle during the pandemic. When borders shut, 62% of low-income countries saw shortages of key antibiotics. The WHO is now pushing for more regional manufacturing hubs to avoid this in the future.

There’s also a quiet tension: the WHO relies on industry-funded clinical trials for 45% of its evidence - up from 28% in 2015. Critics say this risks bias. The WHO insists it has strict conflict-of-interest rules. All 25 members of the 2023 expert committee disclosed their financial ties - 100% compliance. Still, trust is fragile, and transparency is non-negotiable.

What’s Next? More Tools, More Focus

The WHO isn’t resting. In 2023, it launched the Essential Medicines App - downloaded over 127,000 times in 158 countries. It lets pharmacists and health workers check dosing, interactions, and availability on the go. It’s free. It works offline. It’s changing how decisions are made in remote clinics.

It’s also rolling out new guidelines to fight antimicrobial resistance. Starting in 2024, countries are being asked to create “antibiotic stewardship tiers” - like a traffic light system - to limit overuse. And by 2030, the WHO wants to get essential medicine availability in primary care from 65% to 80%. That’s not just a goal. It’s a promise.

Behind every number is a person. A mother in rural Kenya who can now afford her child’s asthma inhaler. A man in Uganda who gets his HIV meds without selling his cow. A nurse in Bangladesh who doesn’t have to choose between two patients because one drug is out of stock.

The WHO Model Formulary doesn’t cure diseases. But it makes sure the tools to cure them are there - when they’re needed most.

Is the WHO Model Formulary legally binding for countries?

No, the WHO Model Formulary is not legally binding. It’s a voluntary guideline. Countries choose whether to adopt it, adapt it, or ignore it. But nearly all low- and middle-income countries use it as the foundation for their own national lists because it’s evidence-based, transparent, and focused on affordability. While not mandatory, its influence is strong - over 150 countries have built their medicine policies around it.

How does the WHO decide which generics to include?

The WHO Expert Committee reviews every medicine using four criteria: public health relevance (30%), efficacy and safety (30%), cost-effectiveness (25%), and programmatic feasibility (15%). A medicine must score at least 7 out of 10 in each category and an overall score of 7.5 or higher. For generics, they must also pass WHO Prequalification - meaning they’ve been tested to match the original drug’s absorption and effectiveness. Only medicines with strong evidence from randomized trials and clear public health impact make the cut.

Are all generics on the WHO list safe?

Generics that have passed WHO Prequalification are considered safe and effective. But not all generics on the market meet this standard. The WHO list only includes those that have been rigorously tested. The problem is that in many countries, substandard or falsified medicines enter the supply chain after leaving the manufacturer. WHO surveillance found 10.5% of essential medicine samples in low-income countries were substandard or fake - mostly antibiotics and antimalarials. The list ensures quality at the source, but local enforcement is critical.

Why doesn’t the WHO list every new drug?

The WHO doesn’t include every new drug because it prioritizes public health impact over novelty. A drug might be scientifically advanced, but if it’s too expensive, has limited use, or doesn’t address a major disease burden, it won’t make the list. Between 2018 and 2022, only 12% of newly approved drugs were added to the 2023 list. The focus is on medicines that save the most lives at the lowest cost - not the most innovative ones.

Can high-income countries like the U.S. benefit from the WHO list?

Yes, but indirectly. U.S. hospitals rarely use the WHO list for domestic formularies - they rely on U.S.-based databases like Micromedex. But the WHO list influences global health programs funded by the U.S., like PEPFAR and USAID. It also sets a benchmark for cost-effectiveness that some U.S. policymakers reference when evaluating drug pricing. The list’s emphasis on generics has helped drive down prices globally, which benefits everyone, including patients in wealthy countries who rely on imported generics.

Daniel Dover

The WHO Model Formulary is one of those quiet miracles of global health. No fanfare, no press releases - just thousands of lives sustained because someone somewhere decided that medicine shouldn’t be a luxury.

Sarah Barrett

It’s staggering how much structural equity is baked into this list - not through coercion, but through sheer moral clarity. The fact that cost-per-QALY is the gatekeeper, not corporate lobbying, is revolutionary. Most formularies are profit matrices. This one’s a lifeline.

And the generics? Not just cheaper - rigorously validated, bioequivalent, traceable. That’s not compromise. That’s precision.

I’ve seen clinics in rural Guatemala where a single vial of insulin costs more than a week’s wages. Then I’ve seen the same vial, identical, sourced through WHO prequalification, priced at 1/10th. That’s not magic. That’s policy.

The 10.5% substandard drug rate in LMICs? That’s the real crisis. The WHO list doesn’t solve supply chains - it exposes them. And that’s why it’s indispensable.

It’s also why the push for regional manufacturing hubs matters. Relying on three countries for 78% of generics is like putting all your eggs in a basket that gets shipped across five oceans.

When the pandemic hit, we didn’t just lose masks - we lost access to the basics. The WHO’s response wasn’t reactive. It was prophetic.

And yet, nobody talks about it. No TikTok trends. No congressional hearings. Just nurses in Bangladesh, pharmacists in Niger, and mothers in Kenya - quietly surviving because someone, somewhere, refused to let profit dictate survival.

This isn’t just a list. It’s the quietest rebellion against inequality the world has ever seen.

Kapil Verma

India makes 60% of the world’s generic medicines. And yet, the WHO still insists on prequalification? Please. We have the best quality control in the world. Our factories supply 40% of the U.S. market - and they’re FDA-approved. Why does the WHO need to micromanage us? We don’t need Western approval to save lives.

This whole system feels like a colonial relic - a white-led committee deciding what’s ‘good enough’ for the Global South. We don’t need your standards. We need your trust.

And don’t get me started on the 12% new drug inclusion rate. You’re not ‘prioritizing impact’ - you’re ignoring innovation. We’re not here to make your budget look good. We’re here to cure.

Stop treating us like children who need your checklist. We’ve been producing life-saving drugs for decades. The world just didn’t notice - until we started exporting them.

Josiah Demara

Let’s be brutally honest - the WHO Model Formulary is a beautiful illusion. Yes, it’s evidence-based. Yes, it’s cost-effective. But it’s also a political tool dressed in white coats.

45% of its evidence comes from industry-funded trials? And you call that ‘transparency’? The same pharma giants that charge $100,000 for a cancer drug in the U.S. are the ones funding the ‘objective’ reviews that get their generics approved in Nigeria? That’s not a formulary. That’s a revolving door.

And don’t pretend the 89% price drop on HIV meds is some altruistic win. It’s because the patents expired. The WHO didn’t lower prices - the market did. And now they’re using that as proof that ‘generics work’ - while quietly ignoring that 90% of those generics are made in India by companies that still charge 10x more in the U.S.

The real problem? The WHO doesn’t regulate pricing. It regulates paperwork. The medicine gets made. It gets shipped. It gets sold. And somewhere, a child in Uganda gets a fake tablet. The WHO didn’t cause that. But it didn’t stop it either.

This isn’t justice. It’s a system optimized for appearance - not outcomes.

Kaye Alcaraz

The WHO list is a quiet revolution in plain sight. No hype. No hashtags. Just science. Just access. Just dignity.

Esha Pathak

Every pill on that list is a whisper of hope echoing across continents. It’s not just chemistry - it’s philosophy. The idea that a child’s life should not be priced by geography… that’s radical. And beautiful.

But here’s the deeper truth: the real medicine isn’t the tablet. It’s the decision to care. The WHO didn’t invent the science. We did. We chose to see each other as human. That’s the real cure.

🌍✨

Mike Hammer

Had no idea the WHO list was this detailed. I thought it was just ‘here’s some drugs we like.’ Turns out it’s a whole system - bioequivalence ranges, QALY math, prequalification checks. Wild.

And the fact that it’s free, offline, and used by nurses in remote villages? That’s next-level practical. No app store needed. Just a phone and a purpose.

Also, 42% of meds now have kid-friendly forms? Huge. I didn’t realize how many kids were getting crushed adult pills before. That’s quiet innovation right there.

Also, I just checked - my local pharmacy in Ohio stocks a generic blood pressure med that’s on the WHO list. Funny how global justice shows up in your medicine cabinet.

Erica Banatao Darilag

thank you for writting this. i didnt know how much work went into this list. its not just a list. its a promise. and its being kept. even when supply chains break. even when money is short. even when no one is looking. its still there. for the people who need it most.

Betty Kirby

Let’s not romanticize this. The WHO list is a bureaucratic masterpiece that ignores the real pain points: corruption, weak regulatory bodies, and the fact that 70% of essential medicines never leave the warehouse in many countries. The list doesn’t fix logistics. It just makes the world feel better about not fixing them.

And let’s talk about the ‘evidence-based’ criteria. Most of the data comes from trials in urban centers with educated patients. What about rural populations with malnutrition, co-infections, or no access to labs? Their physiology isn’t in the model. Their outcomes aren’t counted.

This isn’t equity. It’s a well-designed illusion that lets wealthy nations sleep easy while children in the Sahel still die because a truck broke down on a dirt road.