SSLR Symptom Checker: Is Your Child's Reaction a True Allergy?

Symptom Assessment Tool

This tool helps determine if your child's symptoms after antibiotic use are likely serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR) rather than a true antibiotic allergy. SSLR is common with certain antibiotics but is not an allergy and doesn't require lifelong avoidance.

Results

Enter your child's information above to see if symptoms match serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR).

When a child develops a rash, fever, and swollen joints a week after taking an antibiotic, it’s natural to panic. Many parents and even some doctors jump to the conclusion: antibiotic allergy. But what if it’s not an allergy at all? What if it’s something called a serum sickness-like reaction - a confusing, often misdiagnosed condition that’s not life-threatening, doesn’t require lifelong antibiotic avoidance, and can be easily managed once correctly identified?

What Exactly Is a Serum Sickness-Like Reaction?

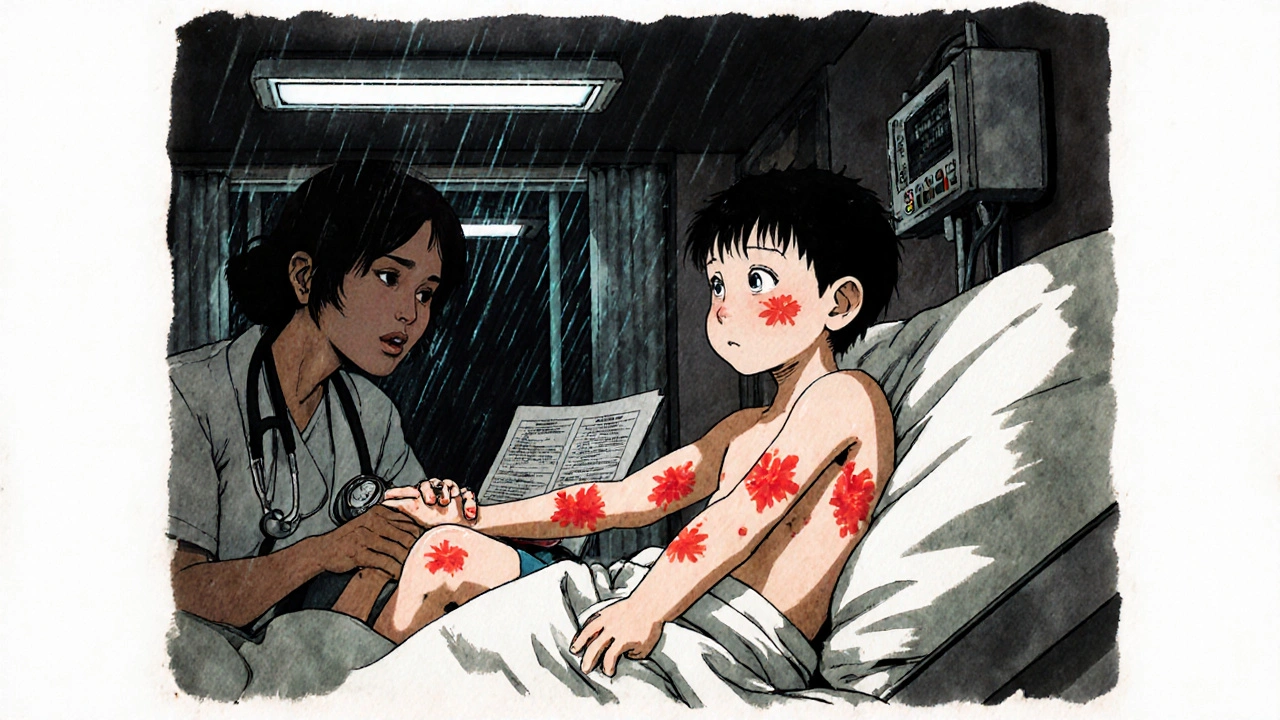

Serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR) is a delayed immune response to certain antibiotics, most commonly cefaclor, and sometimes amoxicillin. It shows up 1 to 21 days after taking the drug, usually around day 7 to 10. Unlike true allergic reactions - which happen within minutes or hours and can cause anaphylaxis - SSLR is slower, milder, and doesn’t involve the same immune pathways. It was first noticed in children in the 1980s, after doctors saw kids getting rashes and joint pain after taking cefaclor. At first, they thought it was classic serum sickness - a reaction from animal-derived antiserum used in the early 1900s. But research from the University of Minnesota in 1987 proved it was different. No immune complexes in the blood. No kidney damage. No vasculitis. Just a strange, self-limiting reaction tied to specific antibiotics. Today, we know SSLR affects mostly children under 6 years old. About 78% of cases happen in this group, according to data from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Adults rarely get it. And while it looks scary - bright red, itchy hives that move around the body, fever, and painful joints - it’s not dangerous in the long term.The Classic Triad: Rash, Fever, Joint Pain

If you’re trying to spot SSLR, look for these three signs together:- Urticarial rash - This isn’t just a simple red patch. It’s raised, itchy, migratory hives that appear, fade within hours, then pop up somewhere else. They can cover the arms, legs, torso, or face. In 95% of cases, this is the first and most noticeable symptom.

- Fever - Usually between 38°C and 39°C. It’s not high enough to suggest a severe infection, but it’s persistent and doesn’t respond to typical fever reducers right away.

- Joint pain or swelling - Often in the knees, wrists, or ankles. It’s symmetric, meaning both sides of the body are affected. Kids might limp or refuse to walk. Parents often mistake this for growing pains or a viral illness.

Why Cefaclor? And Why Kids?

Cefaclor, a second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, is responsible for 65% to 80% of pediatric SSLR cases. Why? It’s not about the drug being “stronger.” It’s about how some children’s bodies break it down. Research from Mount Sinai and DermNet NZ points to a genetic quirk. Some kids have a variant in the CYP2C9 gene - a liver enzyme that helps metabolize drugs. This variant causes cefaclor to linger in the system longer, forming metabolites that trigger the immune response. It’s not an allergy to all cephalosporins - just cefaclor. And it’s not passed down like a typical allergy; it’s a metabolic issue. Amoxicillin is the second most common trigger. But here’s the good news: if your child had SSLR from cefaclor, they can usually take other antibiotics - including other cephalosporins like cephalexin - without issue. Studies show 89% of children tolerate them just fine.How Is SSLR Diagnosed? (And Why So Many Get It Wrong)

There’s no single blood test for SSLR. Diagnosis is clinical: timing of symptoms, exposure history, and ruling out other causes. Doctors need to check for:- Recent antibiotic use (within 1-21 days)

- Triad of rash, fever, joint pain

- No signs of infection (like strep throat or mono)

- Normal complement levels (C3, C4)

- No protein in urine

- No cryoglobulins or vasculitis on biopsy

What Happens If You Keep Giving the Antibiotic?

Don’t. Stop the drug immediately. Continuing it can make the rash worse and prolong symptoms. In most cases, symptoms start improving within 24-48 hours after stopping the antibiotic. But don’t just stop and hope. See a doctor. A pediatric allergist or immunologist can confirm it’s SSLR and not something more serious like Kawasaki disease, Lyme disease, or acute rheumatic fever.Treatment: No Magic Bullet, But Simple Relief

There’s no cure for SSLR - it resolves on its own. But you can make your child more comfortable.- Antihistamines - Second-generation ones like cetirizine (0.25 mg/kg every 12 hours) help with itching. They don’t speed up recovery, but they make the rash bearable.

- NSAIDs - Ibuprofen (10 mg/kg every 8 hours) reduces joint pain and fever. Avoid aspirin in children.

- Corticosteroids - Only for severe cases where joint pain or rash is disabling. Prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day for 5-7 days, then slowly tapered, works well. Most kids don’t need it.

Can They Take Antibiotics Again?

Yes. And they should. A 2023 study from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital followed 127 children who had SSLR. At least 6 months after the reaction, they were given an oral challenge - a supervised dose of the same antibiotic (or another cephalosporin). Results? 92% tolerated it without any reaction. This means: SSLR is not a lifelong allergy. Avoiding all penicillins or cephalosporins is unnecessary and harmful. Only the specific drug that caused the reaction - usually cefaclor - needs to be avoided in the future. One parent on Reddit shared: “My daughter had SSLR after cefaclor. We were terrified. But after an allergist did a challenge at 10 months, she took amoxicillin for her next ear infection - no problem.”What About Vaccines?

No link. SSLR has nothing to do with vaccines. The 2023 AAAAI guidelines explicitly state that children with a history of SSLR can safely receive all routine vaccines, including the rabies vaccine. The incidence of SSLR after rabies vaccine is 0.003% - so low it’s not a concern.

What’s New in 2025?

The medical world is catching up. In 2024, the International Consensus on Drug Hypersensitivity officially gave SSLR its own ICD-11 code: RA43.1. That means it’s now recognized as a distinct condition - not a subtype of allergy. Researchers are also testing a simple urine test to detect cefaclor metabolites. Early results from UC San Francisco show 94% accuracy in distinguishing SSLR from true allergy. This could make diagnosis faster and cheaper, especially in places without allergists. Meanwhile, hospitals like Boston Children’s are testing AI tools that scan electronic records and flag potential SSLR cases. In a 2023 trial, the system caught 88% of true cases and missed only 9% - far better than human documentation.What Should Parents Do?

If your child develops a rash, fever, and joint pain after an antibiotic:- Stop the antibiotic immediately.

- Call your pediatrician - don’t wait.

- Ask: “Could this be a serum sickness-like reaction?”

- Request a referral to a pediatric allergist.

- Insist on accurate documentation: “SSLR triggered by cefaclor,” not “penicillin allergy.”

- Plan for a supervised rechallenge in 6-12 months if needed.

What About Adults?

SSLR is rare in adults. Most cases reported are in children under 6. If an adult develops a similar reaction after an antibiotic, other causes - like drug-induced lupus, viral infections, or true IgE-mediated allergy - are far more likely. Always consult a specialist.Why This Matters

Misdiagnosing SSLR as an allergy isn’t just a medical error - it’s a financial burden. In the U.S. alone, unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use due to SSLR mislabeling costs $187 million a year. It also increases the risk of C. diff infections, antibiotic resistance, and hospitalizations. Correctly identifying SSLR means fewer expensive drugs, fewer side effects, and better outcomes. It’s a simple change with huge ripple effects.Is serum sickness-like reaction the same as a penicillin allergy?

No. A penicillin allergy is an IgE-mediated reaction that happens quickly - within minutes to hours - and can cause anaphylaxis. SSLR is a delayed, T-cell-mediated reaction that occurs days after taking the drug. It doesn’t involve the same immune system pathways and doesn’t mean the child is allergic to all penicillins or cephalosporins. Only the specific drug that caused it needs to be avoided.

Can my child take amoxicillin after having SSLR from cefaclor?

Yes, most can. Studies show 89% of children who had SSLR from cefaclor tolerate amoxicillin and other cephalosporins without issue. A supervised oral challenge by an allergist, usually done 6 to 12 months after the reaction, confirms safety. Only the triggering drug - in this case, cefaclor - needs to be avoided long-term.

How long does a serum sickness-like reaction last?

Symptoms usually start improving within 24 to 48 hours after stopping the antibiotic. Most children feel better in 3 to 7 days. In about 8% of cases, mild rash or joint discomfort can linger for up to 3 months, but it’s not dangerous and resolves on its own.

Should I avoid all antibiotics if my child had SSLR?

No. Only avoid the specific antibiotic that caused the reaction - usually cefaclor. Other antibiotics, including other cephalosporins like cephalexin or amoxicillin, are generally safe. Avoiding all antibiotics unnecessarily increases the risk of more serious infections and promotes antibiotic resistance.

Can SSLR happen again if my child takes the same antibiotic later?

In most cases, no. Studies show that when children are rechallenged with the same antibiotic (like cefaclor) under medical supervision, 92% have no reaction. This suggests the reaction is not due to permanent sensitization. However, if a reaction does recur, then that antibiotic should be permanently avoided.

Is SSLR dangerous?

Not usually. SSLR is uncomfortable and can look alarming, but it doesn’t damage organs or cause long-term harm. It’s not life-threatening like anaphylaxis. The real danger comes from misdiagnosis - leading to unnecessary use of stronger antibiotics, increased risk of side effects, and long-term restrictions on safe, effective treatments.

Jen Taylor

Oh my gosh, I had no idea this was even a thing! My daughter got a crazy rash after cefaclor last year - we were terrified she had some rare autoimmune disorder. Turns out it was SSLR. The doctor just called it ‘allergy’ and now she’s stuck with this stupid label in her chart. I’m so glad someone finally explained the difference between this and real IgE reactions. It’s not an allergy - it’s a metabolic hiccup. And yes, she took amoxicillin last month with zero issues. Thank you for writing this.

Shilah Lala

Wow. Another medical article that sounds like it was written by a pharmaceutical rep who got paid to write ‘don’t panic’ in 12-point font. So what you’re saying is… if your kid breaks out in hives and can’t walk, just shrug and say ‘oh it’s not an allergy’? And then go right back to giving them the same poison? Next you’ll tell me aspirin is fine for kids with fevers. I mean, sure, I trust your 92% statistic - but what about the 8%? Who’s holding the baby when it’s their kid?

Christy Tomerlin

America’s healthcare system is broken. You get one doctor who says ‘allergy’ and now your kid can’t get penicillin for the rest of their life. Meanwhile, in Germany, they just test the metabolites and move on. No drama. No fear. Just science. We’ve turned every rash into a lawsuit waiting to happen. And now we’re overmedicating kids with vancomycin because someone didn’t read a 1987 paper. Pathetic.

Susan Karabin

It’s wild how we panic over a rash but ignore the real problem - how we treat antibiotics like candy. Kids get them for sniffles. Parents demand them. Doctors give them. Then when the body reacts? Oh no, it’s an allergy. But what if the body was just trying to say ‘hey, slow down’? SSLR isn’t the enemy. Overprescribing is. I’ve seen kids on antibiotics for ear infections that cleared up on their own. We’re training immune systems to be confused. This reaction? It’s a warning sign. Not a life sentence.

Lorena Cabal Lopez

92% tolerance rate? That’s statistically meaningless if you’re the 8%. And why are we trusting pediatricians to diagnose this? They’re not allergists. They see a rash, check a box, and move on. I’ve seen kids misdiagnosed with SSLR when it was Lyme. Or Kawasaki. Or even a weird viral thing. This article reads like a marketing brochure for cephalosporin manufacturers. Don’t be fooled.

Stuart Palley

Stop. Just stop. You people are acting like this is some revolutionary breakthrough. It’s been known since the 80s. The fact that doctors still call it ‘penicillin allergy’ means they’re lazy. Or afraid. Or both. I’m a nurse. I’ve seen parents cry because their kid ‘can’t have any antibiotics.’ Meanwhile, the kid’s got pneumonia and we’re giving them azithromycin because the chart says ‘allergic.’ That’s not science. That’s negligence. Fix the system. Not the label.

kendall miles

Did you know the CDC has been quietly tracking SSLR cases since 2019? And guess what? The spikes line up with when Big Pharma pushed cefaclor as a ‘safer’ alternative to amoxicillin. Coincidence? Or a controlled rollout to test immune responses in kids? They knew. They always knew. And now they’re pushing this ‘it’s not an allergy’ narrative to avoid liability. The urine test? It’s not for diagnosis. It’s for insurance denial. Wake up.

Gary Fitsimmons

I’m a dad. My son had this. We were scared. The allergist was calm. Said ‘it’s not an allergy, it’s a glitch.’ Gave us a plan. Stopped the drug. Gave him antihistamines. Two days later he was running around again. We got the right label. We didn’t avoid all antibiotics. We just avoided cefaclor. And now he’s fine. This isn’t scary. It’s fixable. Stop making it worse with fear.

Bob Martin

92% tolerance? Yeah, but what about the kids who get it twice? You think that’s random? The immune system remembers. You think the liver enzyme variant is the only factor? What about gut microbiome? What about concurrent infections? This isn’t a clean-cut answer. It’s a messy biological response. And you’re reducing it to a statistic because it’s easier than admitting we don’t fully understand it. But hey, at least now we have an ICD-11 code. Progress.

Sage Druce

One sentence: Stop calling it an allergy and start calling it what it is - a delayed metabolic hiccup - and you’ll save thousands of kids from unnecessary antibiotic restrictions and resistance.