When you’re running a clinical trial, not every side effect needs the same level of attention. Some reactions are annoying but harmless. Others could mean the difference between life and death. The key is knowing which is which - and when to report each one. Confusing serious with severe is one of the most common mistakes in clinical research, and it costs time, money, and - more importantly - delays real safety alerts.

What Makes an Adverse Event "Serious"?

An adverse event (AE) is any unwanted medical occurrence during a clinical trial, whether or not it’s linked to the drug being tested. But only some AEs are classified as serious. The definition isn’t about how bad the patient feels. It’s about what actually happened to them.

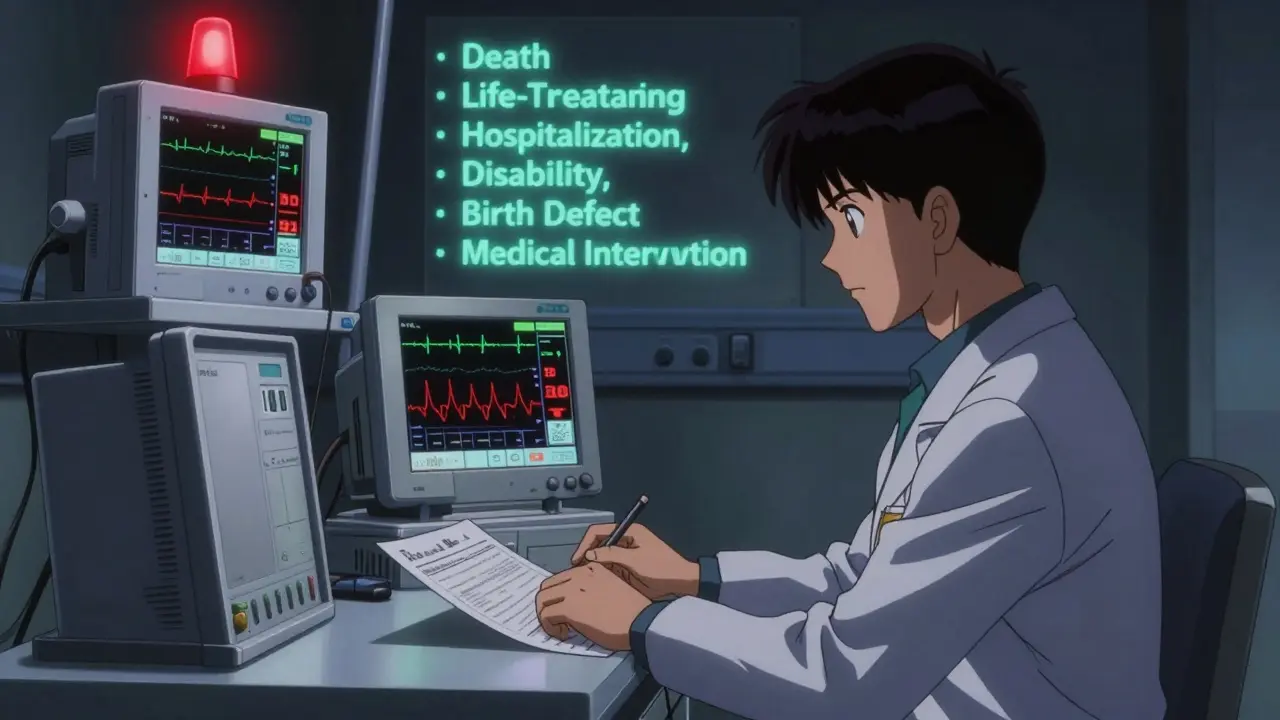

The FDA and ICH E2A guidelines define a serious adverse event (SAE) by six specific outcomes:

- Death

- Life-threatening condition

- Requires hospitalization or prolongs an existing hospital stay

- Results in persistent or significant disability

- Causes a congenital anomaly or birth defect

- Requires medical intervention to prevent permanent damage

If an event doesn’t meet one of these, it’s non-serious - no matter how intense the symptoms. A migraine that knocks someone out for a day? Non-serious. A seizure that leads to a 3-day hospital stay? Serious. A rash that itches? Non-serious. A rash that triggers anaphylaxis and emergency intubation? Serious.

There’s a big difference between severity and seriousness. Severity describes how bad something feels - mild, moderate, or severe. Seriousness describes what the outcome is. A severe headache that goes away with ibuprofen isn’t serious. A mild headache that leads to a stroke? That’s serious.

When Must You Report a Serious Adverse Event?

Timing matters. If a serious event happens, you don’t wait for next week’s meeting. You act fast.

Investigators must report SAEs to the trial sponsor within 24 hours of learning about them - even if they’re not sure the drug caused it. The rule is simple: if it meets one of the six criteria above, report it immediately. This applies to all trials, whether funded by the NIH, a pharmaceutical company, or a university.

Once the sponsor gets the report, they have deadlines too. For life-threatening events, they must report to the FDA within 7 calendar days. For other serious events, they have 15 days. These aren’t suggestions. They’re legal requirements under 21 CFR 312.32.

And it’s not just the FDA. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) need to be notified too - usually within 7 days - so they can decide if the trial should continue, pause, or change protocols.

What About Non-Serious Events?

Non-serious adverse events still need tracking - just not right away. These are recorded in Case Report Forms (CRFs) and summarized in routine reports. Most trials collect them monthly or quarterly, depending on the study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP).

Some mild events - like a slight headache or temporary nausea - might not even be documented unless they happen often or cluster in a group of patients. The goal isn’t to log every sneeze. It’s to spot patterns. If 15 out of 30 participants get the same rash after taking the drug, that’s a signal - even if each case is mild and non-serious.

Importantly, IRBs often don’t need to be told about non-serious events unless they’re part of a larger trend or specified in the study protocol. Many sites only report them during annual continuing reviews.

Why Do People Get This Wrong?

It’s not that researchers don’t care. It’s that the line between severity and seriousness is blurry - especially in complex populations.

Take cancer trials. A patient might already be hospitalized for chemotherapy. If they develop a fever, is that a new serious event? Not necessarily. It might just be a flare-up of their existing condition. But if that fever leads to sepsis and ICU admission? Now it’s serious.

Psychiatric events are another trap. A patient reports "severe anxiety." That sounds scary. But unless it leads to self-harm, hospitalization, or inability to function for weeks - it’s not serious under regulatory definitions. Yet in 2023, Reddit threads from clinical research coordinators showed 89% of respondents struggled with this exact confusion.

Studies back this up. At UCSF, over 42% of AE reports in 2022 needed clarification because someone misclassified severity as seriousness. SWOG Cancer Network found that over 30% of their SAE reports had to be corrected after submission. That’s hundreds of hours wasted every year.

How to Get It Right Every Time

There’s a proven way to avoid mistakes: use the decision tree.

The NIH’s 2018 guidelines give you four yes-or-no questions to ask about every event:

- Did it cause death?

- Was it life-threatening?

- Did it require hospitalization or extend an existing stay?

- Did it cause permanent disability or damage?

If the answer to any of these is yes - it’s serious. Report it now. If not - record it, monitor it, but don’t rush.

Also, use standardized tools. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 grades severity (Grade 1 to 5). But seriousness is judged separately. Most sponsors now use both systems side-by-side.

Training helps. ICH E6(R2) requires all study staff to be trained on these definitions before a trial starts. Top research institutions now require annual refreshers - and 98.7% of them do.

The Bigger Picture: Cost, Waste, and Technology

Getting this wrong doesn’t just slow things down - it costs money. In 2022, the pharmaceutical industry spent $1.89 billion on adverse event reporting. Over 60% of that went to processing events that weren’t serious.

That’s why the FDA and EMA are pushing for change. The EU’s Clinical Trials Regulation (2022) cut cross-border reporting confusion by 35%. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance wants to standardize seriousness rules across diseases. And artificial intelligence? It’s already helping. AI tools now classify SAEs correctly 89.7% of the time - better than humans.

But AI doesn’t replace judgment. It supports it. The final call still needs a trained human. That’s why clear rules, consistent training, and a simple decision tree are still the best tools you have.

What’s Next?

By 2025, the ICH E2B(R4) standard will make electronic reporting global. That means fewer lost reports, faster reviews, and fewer errors. The FDA’s 2024 pilot program using natural language processing to auto-triage reports could cut processing time by nearly half.

But none of this matters if the person entering the data doesn’t know the difference between a severe cough and a life-threatening one. The system is getting smarter. But it still depends on you.

Is a severe headache a serious adverse event?

Not necessarily. A severe headache (high intensity) is not automatically serious. It only becomes serious if it leads to death, hospitalization, permanent brain damage, or requires emergency intervention to prevent disability. If the headache resolves with painkillers and doesn’t disrupt normal function, it’s non-serious.

Do I report an adverse event if I’m not sure it’s related to the drug?

Yes. You report serious adverse events regardless of whether you think the drug caused them. The rule is: if it meets one of the six seriousness criteria, report it. Causality is assessed later by the sponsor and regulators.

Can a mild event become serious later?

Yes. An event that starts as mild - like a rash - can progress. If it later leads to hospitalization or anaphylaxis, it must be reclassified as serious and reported immediately as a new event. Always monitor evolving symptoms.

What if a patient goes to the ER but isn’t hospitalized?

Going to the ER alone doesn’t make an event serious. It only counts if the ER visit was to prevent death, permanent damage, or if the condition met one of the other six criteria (e.g., life-threatening arrhythmia). The NIH clarified in 2023 that ER visits without hospitalization are non-serious unless they meet outcome-based criteria.

Who is responsible for reporting serious adverse events?

The investigator (doctor or research staff at the trial site) must report SAEs to the trial sponsor within 24 hours. The sponsor then reports to regulatory agencies like the FDA. IRBs also need timely notification - usually within 7 days - to assess trial safety.

Justin Fauth

Bro, I’ve seen so many interns panic over a migraine and flag it as an SAE. Like, chill. If the patient takes Tylenol and goes back to binge-watching Netflix, it’s not serious. Stop wasting everyone’s time with noise. The system’s already drowning in false positives.

rahulkumar maurya

One must recognize that the conflation of severity with seriousness reflects a fundamental epistemological failure in contemporary clinical governance. The FDA’s six criteria are not mere guidelines-they are ontological boundaries demarcating the realm of the medically significant from the merely symptomatic. Without this rigor, pharmacovigilance devolves into performative data-entry theatre.

Samuel Bradway

My grandma had a bad headache after her trial med and went to the ER. Didn’t get hospitalized. Didn’t need surgery. Just got some fluids and went home. They still reported it as non-serious-and honestly, that’s right. It’s easy to overreact when you’re scared, but we gotta stick to the rules. Thanks for the clarity.

pradnya paramita

Per ICH E2A, the key differentiator is outcome-based classification, not symptom intensity. CTCAE Grade 4 nausea ≠ SAE unless it leads to dehydration requiring IV rehydration and hospitalization. Many sites still miscode these due to lack of standardized training. Recommend implementing automated CTCAE-seriousness crosswalks in EDC systems to reduce inter-rater variability.

Nathan King

It is, regrettably, not uncommon for clinical research personnel to mistake subjective patient distress for regulatory significance. The distinction between severity and seriousness is not a semantic nicety-it is a legal and ethical imperative. Failure to adhere to the prescribed criteria constitutes a deviation under 21 CFR 312.32 and may expose institutions to audit findings.

Harriot Rockey

This is SO helpful!! 🙌 I used to stress over every little thing-now I just ask: ‘Did it kill them? Hospitalize them? Break something permanently?’ If no → log it, watch it, don’t panic. You’re all doing important work. Keep it up! 💪❤️

Roshan Gudhe

There’s a quiet irony here: we build complex systems to detect danger, yet we often fail to see that the real danger is in our own panic. A headache isn’t a crisis unless it becomes one. The same goes for fear, for bureaucracy, for the urge to report everything. Sometimes, the most responsible act is to wait. To observe. To not rush to judgment.

Rachel Kipps

I think this post is really great, but I keep mixing up the 7 day vs 15 day deadlines... is it 7 for life threating and 15 for others? Or was it the other way around? 😅 Also, do IRBs need the same timeline as FDA? I’m still learning...

Ed Mackey

Just wanted to say thanks for this. I work at a small site and we don’t have a pharmacovigilance team. I used to just guess. Now I’ve got the decision tree printed on my desk. Game changer. No more second-guessing.

Alex LaVey

Big shoutout to the folks in India and the US working through this stuff-different systems, same goal. We’re all trying to keep patients safe. I’ve seen how a simple misclassification can delay a drug that could help thousands. Let’s keep learning from each other.

caroline hernandez

Pro tip: Use the CTCAE severity grade + seriousness criteria as a dual-filter in your EDC. I’ve trained 20+ coordinators this way. 92% reduction in misclassifications in 6 months. Also-teach them to ask: ‘Would this event be flagged if the patient wasn’t in a trial?’ If yes → SAE. If no → non-serious. Simple.

Jhoantan Moreira

Just read this while waiting for my coffee. Seriously? This is the kind of post that makes me proud to be in this field. Clear, practical, and human. Thank you for writing it. 🙏☕