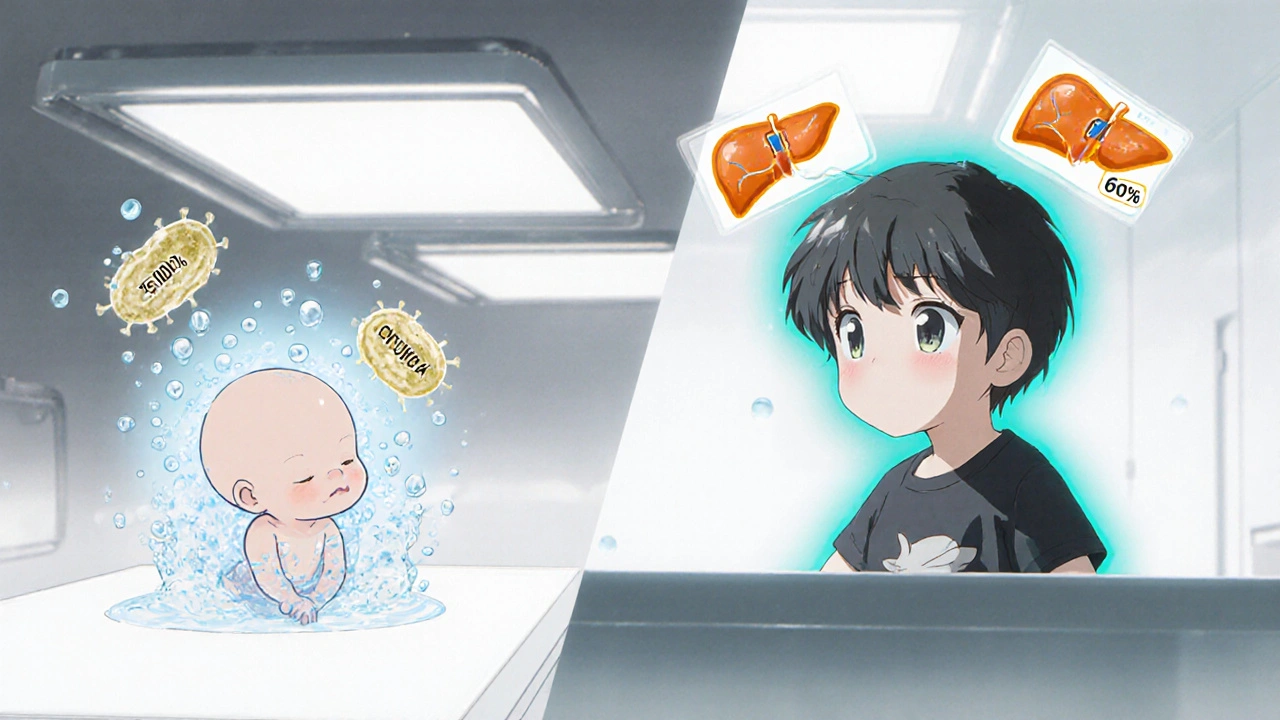

When we talk about pediatric medication side effects are adverse reactions that occur in children because their bodies process drugs differently than adults, we’re dealing with a complex mix of growth, metabolism, and genetics.

Why Children React Differently

Kids are not just “small adults.” Their body composition shifts rapidly-infants are 75‑80% water, while adults hover around 60%. Liver enzymes such as CYP450 mature at different ages, meaning a drug cleared in seconds by a teenager could linger for hours in a newborn. Transport proteins that move medicines into cells also change, creating windows of vulnerability during the first two years of life.

Weight‑based dosing (mg/kg) tries to account for size, but it can’t fully capture the developmental stage. For example, neonates have only 30‑40% of adult cytochrome activity, yet some infants (1‑12 months) temporarily exceed adult levels for certain enzymes, leading to faster clearance and sometimes sub‑therapeutic exposure.

How Big Is the Problem?

According to a 2023 Columbia University study led by Dr. Nicholas Giangreco, pediatric drug‑related side effects cause nearly 10% of childhood hospitalizations, and half of those cases are life‑threatening. The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System logged over 264,000 pediatric reports between 2018‑2022. In hospitals, up to 18% of admitted children experience at least one adverse drug event, compared with 6.7% in adult patients.

Serious reactions are more common in kids than adults: around 50% of pediatric adverse events are classified as serious, versus roughly one‑third in adults. Certain drug classes-antihistamines, antibiotics, and psychiatric medications-show especially high pediatric risk profiles.

High‑Risk Drugs You Should Know

- Montelukast is a leukotriene receptor antagonist used for asthma. In children’s second year of life it carries a 3.2‑fold increased risk of psychiatric side effects, including agitation and vivid dreams.

- Loperamide is an anti‑diarrheal. In kids under 6 it can trigger fatal cardiac arrhythmias; the KIDs List flags it as potentially inappropriate.

- Aspirin is linked to Reye’s syndrome when given to children with viral infections, occurring in about 1 in 1,000 cases.

- Codeine is metabolized by CYP2D6. Roughly 1 in 30 children are ultra‑rapid metabolizers, putting them at risk of respiratory depression.

- Benzocaine in teething gels can cause methemoglobinemia; the FDA recorded over 400 cases between 2006‑2011.

Side‑Effect Frequency: Kids vs. Adults

| Drug Class | Typical Side‑Effect in Children | Typical Side‑Effect in Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Antihistamines | Central nervous system sedation (15‑20%) | Sedation (5‑10%) |

| Antibiotics | Gastro‑intestinal upset (25‑30%) | GI upset (10‑15%) |

| Psychiatric meds | Severe reactions (2‑3× higher risk under 12) | Standard risk |

Recognizing and Managing Side Effects

Most mild reactions-headache, nausea, mild rash-appear within the first few days and often resolve on their own. Parents should keep a medication diary, noting dose, time, and any new symptoms. If a child develops:

- Difficulty breathing (0.1‑0.5% of courses)

- Facial swelling (0.05‑0.2%)

- Rapid heart rate not explained by the drug’s known profile

call emergency services immediately. For moderate issues like persistent vomiting or a rash covering >10% of body surface, contact the prescribing clinician-dose reduction (usually 25‑50%) may be recommended.

Tools, Resources, and Guidelines

The Pediatric Drug Safety portal (PDSportal) is a free database launched in 2023 that aggregates safety signals across developmental stages. The KIDs List (Key Potentially Inappropriate Drugs in Pediatrics) from Mayo Clinic highlights drugs with elevated risk.

Regulatory frameworks such as the FDA Modernization Act (1997) and the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (2002) require pediatric studies for new drugs, yet only about half of adult‑approved drugs have pediatric labeling.

For clinicians, the FDA’s MedWatch program allows voluntary reporting of adverse events; in 2022 it received 12,347 pediatric reports, with antibiotics accounting for 48% of those.

Future Directions: Precision Pediatric Pharmacology

Research is moving toward age‑specific pharmacogenomic guidelines. A 2024 NIH‑funded study (R01‑GM141804) aims to create dosing charts that incorporate CYP450 genotype, age, and weight. Early modeling suggests that such precision could prevent up to 30,000‑50,000 hospitalizations each year.

Meanwhile, the KidsSIDES database (2023) now lists 1,847 validated drug‑side‑effect pairs, giving clinicians a powerful decision‑support tool. As more pediatric trials are mandated, we expect a steady rise in label updates-over 700 changes since 1998.

Quick Checklist for Parents and Caregivers

- Ask the prescriber if the drug has pediatric labeling.

- Track every dose and any new symptom in a diary.

- Know the red‑flag symptoms (breathing trouble, swelling, fast heartbeat).

- Be aware of high‑risk drugs on the KIDs List.

- Report serious reactions to MedWatch or your local health authority.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes a medication “off‑label” for children?

Off‑label means the drug has not been formally studied or approved for a specific age group, dosage, or condition in children. Doctors may still prescribe it based on clinical judgment, but the safety data are limited.

How can I tell if a side effect is serious?

Serious side effects often involve breathing difficulty, facial swelling, uncontrolled fever, or a rapid heartbeat that isn’t expected. If any of these appear, seek emergency care right away.

Are antibiotics more risky for kids than adults?

Yes. About 25‑30% of children on antibiotics experience GI upset, compared with 10‑15% of adults. Some classes, like high‑dose amoxicillin‑clavulanate, carry a 2.7‑fold higher risk of severe gut reactions in children under two.

What should I do if my child needs a medication flagged on the KIDs List?

Talk to the prescriber about alternatives. For example, loperamide can often be replaced with oral rehydration solutions, and aspirin can be swapped for acetaminophen when treating fever.

Where can I report a suspected drug reaction?

Use the FDA’s MedWatch online form or call 1‑800‑FDA‑1088. Provide the drug name, dose, child’s age, and a description of the reaction.

Brady Johnson

Man, the whole pediatric drug saga is a textbook case of reckless optimism gone rogue. You read about the fancy dosing charts and think everything's under control, but the reality is a toxic avalanche waiting to happen. Kids aren't just tiny adults; their enzymes are a rollercoaster that can turn a safe medication into a death sentence in a blink. The statistics you quoted are chilling – nearly one in ten hospitalizations because a kid's body couldn't handle the chemical onslaught. And don't get me started on the off‑label prescriptions that fly under the radar like secret weapons. It's like handing a loaded gun to a toddler and hoping they won’t pull the trigger. The FDA reports are a litany of warnings that get buried under corporate PR fluff. Every time a new drug gets a pediatric label, I wonder how many hidden side‑effects are still simmering beneath the surface. The enzyme maturation timeline is a minefield; a drug cleared in seconds for a teen can linger for hours in a newborn, turning therapeutic doses into toxic overload. Parents are left juggling medication diaries, hoping they won’t miss that subtle shift from mild rash to life‑threatening anaphylaxis. The KIDs List is a start, but it feels like a band‑aid on a gaping wound. We need a paradigm shift, not just incremental tweaks. Until we demand transparent, age‑specific pharmacokinetic data, kids will continue to pay the price for adult‑centric drug development. In short, the system is a ticking time‑bomb and we’re all holding the match.

Jay Campbell

I can see the effort put into gathering all that data, and it really helps clinicians make more informed choices for our kids. The side‑effect tables are especially useful for spotting trends early. It’s good to know there are resources like the Pediatric Drug Safety portal out there. Let’s keep sharing these tools so everyone stays on the same page.

Laura Hibbard

Wow, so much to digest-feels like a pharma‑conspiracy novel, right? The way they hype up a new antibiotic and then whisper about GI upset in kids is classic. I love how the article doesn’t shy away from the scary stats, but still, you can’t help but roll your eyes at the industry’s optimism. Kids are basically experimental subjects for a market that loves to push boundaries. Even the “quick checklist” reads like a survival guide for a war zone. If only every pediatrician got this level of detail, maybe we’d see fewer emergency calls. Still, kudos for pulling together the numbers. It’s a lot clearer now why Montelukast’s psychiatric side‑effects freak me out.

Rachel Zack

Seriously, prescribing medications without solid pediatric data is just reckless. The moral of the story? We need stricter regulations and more transparent studies. I cant believe some doctors still rely on adult dosing tricks for children. It's not just a small oversight; it's a huge ethical breach that puts our kids in danger. I hope future guidelines finally put children first.

Lori Brown

What a comprehensive read! 🌟 I feel more empowered to ask the right questions at the pharmacy now. Knowing the red‑flag symptoms can truly be a lifesaver. Thanks for breaking down the complex stuff into bite‑size nuggets. Keep up the great work! 😊

Nic Floyd

Let me unpack this from a pharmacokinetic perspective the article highlights the ontogeny of CYP450 isoforms which is paramount for dose optimization in pediatrics the variability in hepatic clearance rates underscores the necessity for physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling that integrates age‑dependent enzyme expression data moreover the population pharmacodynamics insights reveal a steep concentration‑effect curve for certain psychotropic agents especially in the 2‑5 year cohort which raises safety flags the KIDs List serves as a decision‑support adjunct but should be complemented by therapeutic drug monitoring especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices like codeine the article’s emphasis on adverse event reporting aligns with the WHO’s pharmacovigilance framework however there remains a gap in real‑world evidence capture especially in community settings the integration of electronic health records with MedWatch could streamline signal detection further the recent NIH grant aims to generate genotype‑guided dosing algorithms which could revolutionize precision paediatrics the challenge will be translating these algorithms into bedside practice without overburdening clinicians the educational component is critical to ensure prescribers understand the nuances of enzyme polymorphisms for drugs like loperamide and benzocaine the future looks promising if stakeholders invest in robust pediatric trials 🚀🥼

Erin Leach

Seeing all these stats really hits home. As a parent, keeping a medication diary sounds like a good habit, even if it feels tedious. Knowing the exact signs to watch for, like rapid heartbeat and swelling, can make a huge difference. It’s reassuring that there are resources out there to report serious reactions. I’ll definitely share this info with other moms in my circle.

Jennyfer Collin

One cannot help but notice the systemic under‑currents of corporate influence shaping these guidelines. The deployment of “high‑risk” drug lists appears more like a public relations maneuver than a genuine safety initiative. While the article references FDA data, it omits the fact that many of these reports are vetted by the very entities that profit from the drugs in question. It is imperative that independent oversight be instituted, lest we continue to gamble with our children’s health under the guise of scientific progress.

Kasey Marshall

Interesting points raised earlier - the balance between necessary medication and risk is delicate. From a practical standpoint, the emphasis on diary keeping is spot on, and the data on enzyme maturation really underscores why one‑size‑fits‑all dosing fails.

Dave Sykes

Stay sharp, keep looking out.

Erik Redli

All this hype about safety feels like a smokescreen. If we really cared, we’d stop pushing off‑label meds and start demanding real pediatric trials. The statistics you share are just numbers that companies use to mask their negligence.

Tim Waghorn

To address the concerns raised, it is essential to adhere to rigorous standards when evaluating drug safety data. The methodological transparency of adverse event reporting must be enhanced, ensuring that all relevant variables are documented with precision. Moreover, collaboration between regulatory agencies and independent research institutions can mitigate potential biases inherent in industry‑sponsored studies.