When you hear the word biosimilar, you might think it’s just a cheaper version of a biologic drug-like a generic pill but for injectables. But that’s not quite right. Unlike generics, which are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs, biosimilars are made from living cells. They’re designed to be highly similar to the original biologic, but tiny differences in how they’re made can change how your body reacts to them. One of the biggest concerns? Immunogenicity-the chance your immune system will see the drug as a threat and start attacking it.

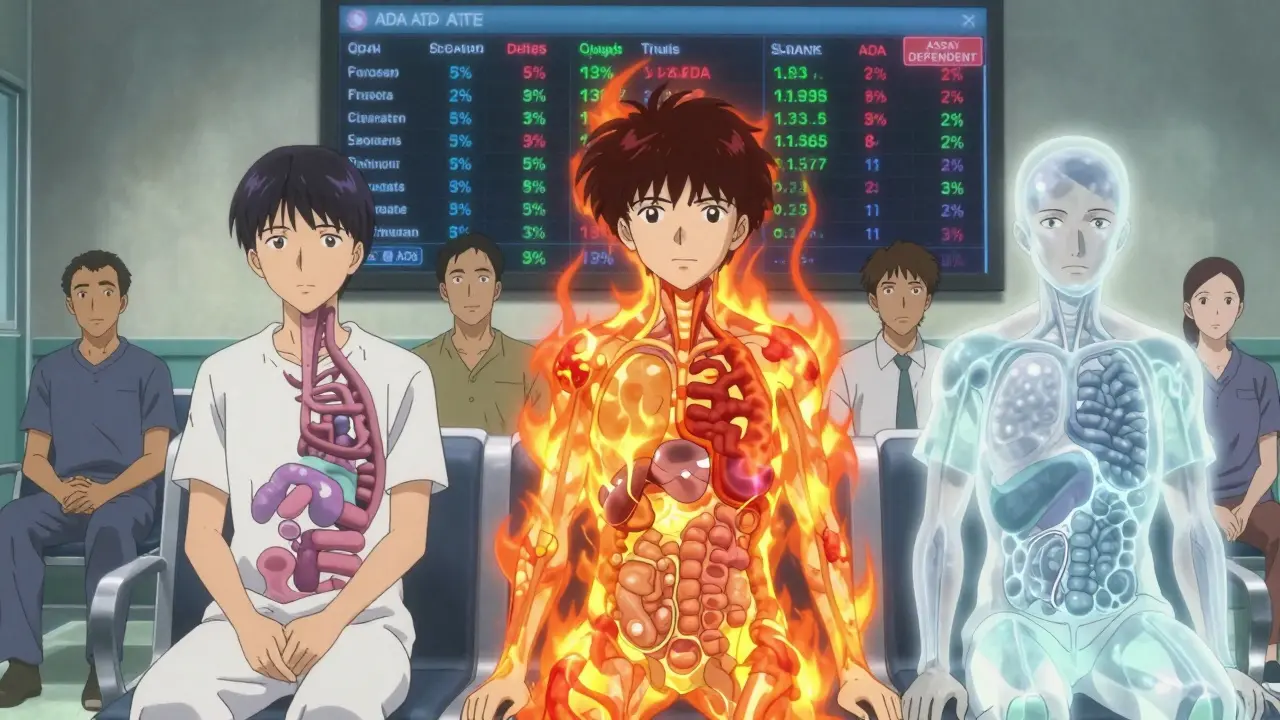

What Is Immunogenicity, Really?

Immunogenicity means your body makes antibodies against the drug. These are called anti-drug antibodies, or ADAs. For most people, this doesn’t cause problems. But for some, those antibodies can block the drug from working, or worse-trigger serious side effects like allergic reactions, infusion reactions, or even loss of disease control. Take cetuximab, a cancer drug. Some patients developed life-threatening anaphylaxis because of a sugar molecule (galactose-α-1,3-galactose) stuck to the drug. It wasn’t the protein itself-it was a tiny, unintended change in how it was made. That’s the kind of thing that keeps regulators up at night. Biosimilars aren’t supposed to do this. But because they’re made in cell cultures-often Chinese hamster ovary cells-there’s room for variation. A change in temperature, pH, or nutrient mix during production can alter how proteins fold, how sugars attach, or whether tiny clumps form. These aren’t mistakes. They’re normal in biologics. But even a 1-2% difference in glycosylation (the sugar coating on proteins) can make your immune system notice something’s off.Why Biosimilars Might Trigger Different Reactions

It’s not just about the drug itself. Your body matters too. And so does how you get the drug. Route of administration: If a drug is injected under the skin (subcutaneous), your immune system has more time to see it. That’s why subcutaneous biosimilars have a 30-50% higher risk of triggering ADAs than IV versions. Think of it like leaving a stranger at your front door versus having them walk right into your living room. Dosing schedule: Taking a drug every few weeks gives your immune system time to notice and remember it. Continuous infusions? Less chance. Intermittent dosing can increase ADA risk by about 25%. Your immune system: People with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis are already primed to react. Studies show they’re more than twice as likely to make antibodies against biologics than healthy people. If you have a certain gene variant-like HLA-DRB1*04:01-you’re nearly five times more likely to respond to some drugs with ADAs. Other meds you’re taking: Methotrexate, a common arthritis drug, cuts ADA rates by 65% when taken with TNF inhibitors. Why? It quietly dampens the immune response. That’s why some doctors always pair biologics with it. And then there’s the manufacturing. Host cell proteins-leftover bits from the cells used to make the drug-can act as triggers. If there’s more than 100 parts per million, ADA rates jump 87%. Protein aggregates? If they make up more than 5% of the product, immunogenicity risk triples.

Are Biosimilars Really Different From the Original?

Here’s the messy part: real-world data doesn’t always match what we expect. In the NOR-SWITCH trial, patients switched from originator infliximab to its biosimilar CT-P13. The biosimilar group had slightly higher ADA rates (11.2% vs. 8.5%). But no one got sicker. No one lost response. The difference was statistical, not clinical. A 2020 study on adalimumab found something more surprising: the biosimilar (Amgevita) had higher ADA rates than Humira-23.4% vs. 18.7%. But again, disease control stayed the same. Patients didn’t flare more. They didn’t need more drugs. Meanwhile, a big study of 1,247 rheumatoid arthritis patients found no difference in ADA rates between originator and biosimilar infliximab. Same numbers. Same outcomes. On Reddit, patients report wildly different experiences. One person had severe injection site reactions after switching to a biosimilar etanercept. Another switched between biosimilars and originators for three years and felt zero difference. So what’s going on? The answer lies in how we test for immunogenicity. Not all tests are created equal. Some use electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays that detect ADAs in 13% of patients. Others use older ELISA methods and catch only 5%. If one study uses ECL and another uses ELISA, you’re not comparing apples to apples-you’re comparing apples to oranges. Regulators know this. The EMA and FDA both say: if you want to prove a biosimilar is similar, you must test it side-by-side with the original using the exact same assay. No shortcuts.What’s Changing in the Industry

The market is growing fast. In 2022, biosimilars brought in $10.5 billion globally. By 2028, that’s expected to hit $34.5 billion. In Europe, 85% of infliximab prescriptions are now biosimilars. In the U.S., it’s only 45%. Why the gap? Legal battles, pharmacy benefit managers, and fear. But fear is fading. More real-world data is coming in. And technology is getting better. Next-generation tools like advanced mass spectrometry can now map protein structures with 99.5% accuracy. That means we can spot tiny glycosylation differences before the drug even hits the market. Some labs are already combining proteomics, glycomics, and immunomics-looking at the protein, its sugars, and how immune cells react to it-all at once. The FDA warns that even small changes in the Fc region (the part of the antibody that talks to immune cells) can alter function. A difference under 5% might not affect efficacy, but in a sensitive patient, it could still trigger a response. That’s why the next wave of biosimilars won’t just be “similar.” They’ll be engineered to be less immunogenic. Some are being designed with human cell lines instead of hamster cells to reduce foreign sugars. Others are using better purification methods to cut host protein contaminants by 90%.

What This Means for Patients

If you’re on a biologic and your doctor suggests switching to a biosimilar, don’t panic. The evidence shows most people switch without issue. But pay attention. Watch for new symptoms: unexplained fatigue, fever, swelling at the injection site, or a sudden loss of response. Tell your doctor. It might not be the drug-but it might be. If you’ve had a bad reaction to one biosimilar, it doesn’t mean you’ll react to all of them. Each one is different. Just like not all aspirin brands give you a stomachache. And if you’re worried? Ask your doctor: “What assay are they using to test for antibodies?” If they don’t know, it’s a red flag. Proper monitoring matters.The Bottom Line

Biosimilars aren’t perfect copies. But they’re not random imitations either. They’re carefully engineered to match the original as closely as science allows. Immunogenicity is real-but it’s not inevitable. For most people, the risk is low. For a few, it’s manageable. The bigger story? Biosimilars are saving lives and cutting costs. In the U.S., a single biosimilar adalimumab can save patients $10,000 a year. That’s not just money-it’s access. More people can get the drugs they need. The goal isn’t to find a drug that’s identical. It’s to find one that works just as well, safely, and affordably. And so far, the data says: they do.Can biosimilars cause more side effects than the original biologic?

In most cases, no. Large clinical trials and real-world studies show that biosimilars have similar safety profiles to their reference products. While minor differences in immune response can occur-like slightly higher ADA rates in some studies-these rarely translate into more side effects or worse outcomes. The FDA and EMA require rigorous testing to ensure no clinically meaningful differences exist.

Why are biosimilars cheaper than biologics if they’re so complex to make?

Biosimilars don’t need to repeat the full clinical trials that the original biologic went through. Developers can rely on the original’s safety and efficacy data, focusing instead on proving similarity through analytical, functional, and limited clinical studies. This cuts development costs significantly. Manufacturing is still expensive, but competition drives prices down-often by 30-70% compared to the originator.

Do all biosimilars have the same risk of immunogenicity?

No. Each biosimilar is unique. Differences in cell lines, purification methods, stabilizers (like polysorbate 20 vs. 80), and formulation can affect immunogenicity. Even small changes in sugar patterns or protein aggregates can make one biosimilar more likely to trigger antibodies than another-even if both are approved as similar to the same reference product.

Can switching from a biologic to a biosimilar cause loss of effectiveness?

In most patients, switching doesn’t cause loss of response. Trials like NOR-SWITCH and multiple registry studies show comparable disease control after switching. However, a small subset of patients-especially those with prior immunogenicity or complex disease histories-may respond differently. Doctors often monitor patients closely after a switch, especially in the first few months.

How do doctors test for immunogenicity?

Doctors use a tiered approach: first, a screening test (like ECL or ELISA) to detect any antibodies. If positive, a confirmatory test checks if those antibodies are specific to the drug. Finally, a neutralizing antibody test determines if the antibodies block the drug’s function. These tests are usually done in specialized labs and aren’t routine unless a patient loses response or has an allergic reaction.

Alex Curran

Interesting breakdown on glycosylation differences - honestly didn't realize a 1-2% shift in sugar chains could trigger ADAs. The subcutaneous vs IV point is huge too. I've seen patients flare after switching to SC biosimilars even when their IV response was perfect. It's not about the drug being 'worse' - it's about delivery kinetics and immune exposure time. Also, host cell proteins >100 ppm? That's wild. Labs need better QC standards.

Jedidiah Massey

Let’s be real - if you’re using ELISA assays to monitor ADA in a clinical setting, you’re doing it wrong. ECL is the gold standard, period. The fact that some institutions still rely on outdated methods is why we get conflicting data. And don’t get me started on how PBM’s push biosimilars without even knowing the assay platform. It’s a regulatory nightmare wrapped in a cost-saving veneer. 🤦♂️

Lynsey Tyson

I switched from Humira to a biosimilar last year and felt zero difference. No flare, no fatigue, no weird rashes. But my friend had a nasty reaction to the same one - swelling, fever, the whole thing. It’s weird how personal it is. Like how some people get stomachaches from one brand of ibuprofen and not another. I think we need to stop treating biosimilars like they’re all the same. They’re not.

Mark Able

Wait so you’re telling me someone could have a life-threatening reaction because of a sugar molecule? Like… from a hamster cell? That’s insane. Why aren’t we using human cells for everything? This sounds like a horror movie plot. Someone’s gonna die because of a protein that looks like it was made in a lab with a bad coffee stain.

Dikshita Mehta

One thing often missed: methotrexate isn’t just reducing ADA - it’s modulating the entire immune environment. That’s why combo therapy works so well. Also, HLA-DRB1*04:01 carriers? They’re not ‘high risk’ - they’re just biologically wired to respond differently. We need genetic screening before biologic initiation. Not after a reaction. Prevention > reaction.

James Stearns

It is imperative to underscore that the regulatory framework governing biosimilar approval, while ostensibly rigorous, remains fundamentally insufficient in addressing the nuanced immunological heterogeneity inherent in biologic therapeutics. The current paradigm of analytical comparability, while statistically robust, fails to account for dynamic patient-specific immune responses, thereby exposing vulnerable populations to unforeseen clinical consequences. One must question the ethical implications of mass substitution without individualized immunological profiling.

William Storrs

Don’t let the fear of ADAs stop you from switching. Most people do just fine. If you’re worried, talk to your rheumatologist - ask about the assay, ask about your history, ask about methotrexate. You’ve got options. You’re not just a statistic. You’re a person with a treatment plan. And you deserve to feel safe. I’ve seen people go from 80% pain to 20% pain after switching - and save $10k a year. That’s life-changing.

Edington Renwick

Someone’s gonna die from this. Not someday. Soon. You think it’s just ‘slightly higher ADA rates’? That’s what they said about Vioxx. And thalidomide. And now we’ve got biosimilars being pushed because they’re cheaper, not because they’re safer. And patients are being told to ‘just monitor’ like it’s a minor cold. This isn’t science - it’s capitalism with a lab coat.