Joint Load Calculator

This calculator shows how much joint stress is reduced by weight loss. Knee joints experience 1.5× your body weight with each step when at normal weight. Each extra pound adds approximately 4 pounds of pressure to the knees.

Current Joint Load

Your knee joints experience 0.00× your body weight per step.

After Weight Loss

After losing 0.00% of your weight, your joint load will be 0.00× your body weight per step.

Key Takeaways

- Excess body weight adds mechanical stress and triggers inflammation that breaks down cartilage.

- Obesity dramatically raises the risk of osteoarthritis, especially in knees, hips, and the lower back.

- Even modest weight loss (5‑10% of body weight) can halve joint‑loading forces and relieve pain.

- Low‑impact activities like swimming, cycling, and walking are safest for protecting joints while you shed pounds.

- Professional support-physiotherapy, nutrition counseling, and medical‑grade injections-boosts long‑term joint health.

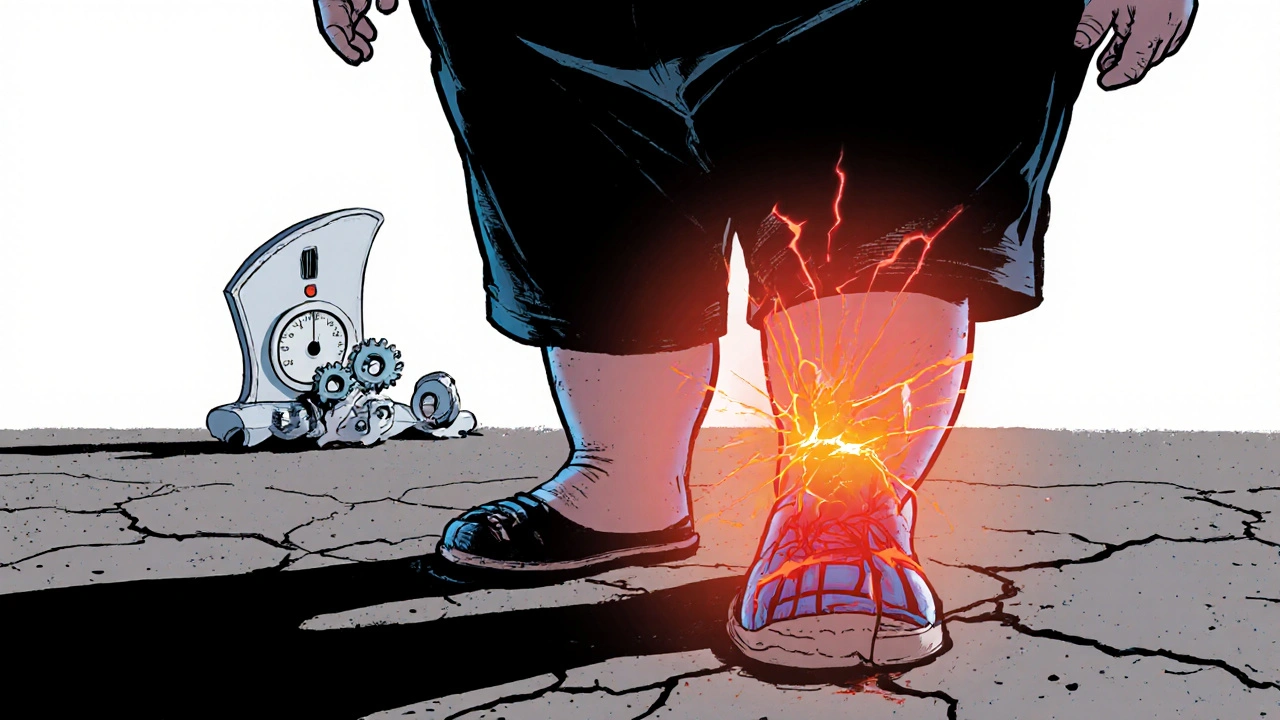

Obesity rates have climbed steadily worldwide, and so have visits to orthopaedic clinics for joint pain. The link isn’t just a coincidence; carrying extra kilos forces your skeleton to work harder and fuels a chronic inflammatory state that attacks the very tissue protecting your bones. If you’re wrestling with a higher obesity number on the scale, you’re also likely to notice creaking knees, stubborn hip aches, or a sore lower back. Understanding why the extra weight hurts your joints-and what you can do about it-can stop the damage before it becomes irreversible.

How Excess Weight Impacts Joints

Obesity is a medical condition characterized by excessive body fat, typically measured by a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher. It increases the load on weight‑bearing joints and triggers systemic inflammation. The twofold assault on joints comes from mechanical stress and metabolic inflammation.

Mechanically, every extra pound adds roughly four pounds of pressure to the knees each step you take. Over time, this amplified load wears down the protective layer of cartilage a smooth, rubbery tissue that cushions bones at joints. When cartilage frays, bones rub together, producing pain and stiffness.

Metabolically, excess fat releases pro‑inflammatory cytokines-think of them as tiny messengers that keep the immune system on high alert. This low‑grade inflammation a chronic state where the body’s defense system continuously releases chemicals that can damage tissues accelerates cartilage breakdown and impairs the body’s ability to repair joint damage.

When you factor in a high BMI body mass index, a ratio of weight to height used to categorize weight status, the odds of developing osteoarthritis jump dramatically. Studies show people with a BMI over 35 are up to six times more likely to need joint replacement surgery compared with individuals of normal weight.

Joint Problems Commonly Linked to Obesity

The most frequent conditions are:

- osteoarthritis a degenerative joint disease marked by cartilage loss, bone spurs, and joint pain, especially in the knees and hips.

- knee pain often described as aching, grinding, or a feeling of the joint giving way, the earliest sign of overload.

- hip joint pain that radiates to the groin or side of the thigh, worsening after prolonged walking or standing.

- lower back pain caused by excess abdominal mass shifting the pelvis and straining spinal discs.

These issues often appear together because the same load‑bearing joints are stressed simultaneously. The knee, for example, bears roughly 60% of total body weight during walking and up to 300% during stair climbing. Throw in obesity and the forces skyrocket, making the knee the most common site for weight‑related joint damage.

Spotting Early Warning Signs

Before the pain becomes chronic, your body sends clues:

- Stiffness after sitting or waking up-usually lasting more than 30 minutes. \n

- A dull ache that eases with movement but returns after rest.

- Swelling or a feeling of warmth around the joint.

- Reduced range of motion; you can’t fully straighten or bend the joint.

If you notice any of these, it’s a signal to act now. Early intervention-through weight loss and joint‑friendly exercise-can halt or even reverse cartilage wear.

Weight‑Loss Strategies That Lighten Joint Load

Even a modest reduction of 5‑10% of body weight can cut knee‑joint forces by up to 40%. Here’s a practical roadmap:

- Nutrition tweak: Swap refined carbs for fiber‑rich vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats. A daily 500‑calorie deficit typically leads to a pound loss per week.

- Track progress: Use a reliable app to log meals and activity. Monitoring calories keeps you accountable.

- Mindful eating: Practice portion control-use half‑plate rule: half vegetables, quarter protein, quarter carbs.

- Hydration: Aim for 2‑3 liters of water daily; it helps curb appetite and supports joint lubrication.

Combine diet with low‑impact movement to protect joints while you shed pounds.

Safe Exercise Options for Overweight Individuals

Choosing activities that minimize joint stress is crucial. Below is a quick guide:

- Swimming or water aerobics - buoyancy supports up to 90% of body weight, letting you move freely.

- Stationary cycling - provides cardio without the impact of running.

- Elliptical trainer - mimics walking but with smooth gliding motion.

- Walking on a soft surface - start with 10‑minute intervals, gradually increasing duration.

- Resistance band exercises - strengthen supporting muscles without heavy loads.

Consistency beats intensity. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate activity per week, broken into manageable sessions.

Medical Support and Treatment Options

If pain persists despite lifestyle changes, professional help can bridge the gap.

- physiotherapy a structured program of exercises and manual techniques to improve joint function and reduce pain customizes movements that strengthen muscles around the joint, reducing load.

- Viscosupplementation - injections of hyaluronic acid lubricate the joint, offering temporary relief.

- Anti‑inflammatory medications - NSAIDs can manage flare‑ups but should be used under medical guidance.

- Weight‑loss surgery - bariatric procedures are considered when BMI exceeds 40 and lifestyle measures fail.

- Joint replacement - reserved for end‑stage osteoarthritis where pain limits daily activities.

Each option has benefits and risks; a shared‑decision approach with your doctor ensures the right fit for your health status.

Comparison of Joint Stress by BMI Category

| BMI Category | Average Load per Step | Risk of Osteoarthritis | Typical Pain Score (0‑10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (18.5‑24.9) | 1.5× | Low | 1‑2 |

| Overweight (25‑29.9) | 2.0× | Moderate | 3‑4 |

| Obese (30‑34.9) | 2.5× | High | 5‑6 |

| Severe Obesity (≥35) | 3.0× | Very High | 7‑9 |

Notice how a 10‑pound loss can shift you from the “Severe Obesity” row to the “Obese” row, cutting the joint load by roughly 15%.

Practical Tips for Everyday Joint Protection

- Wear supportive shoes with good arch support to distribute foot pressure.

- Use a cane or walking pole when navigating stairs or uneven terrain.

- Apply heat before gentle stretching and ice after activity to manage inflammation.

- Maintain a balanced diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids (salmon, walnuts) that naturally reduce inflammation.

- Schedule regular check‑ups with a physiotherapist to adjust exercise plans as you progress.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a slight weight loss really improve joint pain?

Yes. Research shows that losing just 5‑10% of body weight can reduce knee joint load by up to 40%, often translating into noticeable pain relief within weeks.

Is osteoarthritis inevitable for people with obesity?

No. While obesity dramatically raises risk, proactive weight management, targeted exercise, and anti‑inflammatory nutrition can prevent or delay the onset of osteoarthritis.

Which exercise is safest for a beginner with knee pain?

Water‑based activities like swimming or aqua‑aerobics are ideal because the buoyancy removes most of the weight from the joints while still providing resistance.

Do anti‑inflammatory drugs cure joint damage caused by obesity?

They can relieve pain and reduce swelling temporarily, but they don’t repair cartilage. Sustainable improvement comes from weight loss and strengthening the muscles around the joint.

When should someone consider joint replacement surgery?

When pain interferes with daily activities despite weight‑loss efforts, physiotherapy, and medication, and imaging shows severe cartilage loss, a surgeon may recommend replacement.

Take charge of your joint health today: trim the excess pounds, move wisely, and seek professional guidance when needed. Your joints will thank you with smoother steps and fewer aches for years to come.

Steven Waller

Understanding the connection between weight and joint health is the first step toward lasting change. When you view your body as a partnership rather than an adversary, the motivation to make sustainable adjustments grows. Small, consistent choices-like swapping sugary drinks for water or adding a brief walk after meals-compound over time and reduce joint stress. Remember that progress is personal; compare yourself only to your own previous baseline, not to others. By fostering compassion for yourself, you create a supportive environment where your joints can recover and thrive.

Puspendra Dubey

Life’s a grand stage, and our bodies are the actors trapped in a heavy costume we didn’t choose :) When the scales tip, the knees start whispering riddles of pain, like ancient gods demanding tribute. It feels like the universe is testing us, but maybe it’s just a reminder that we cant ignore the signals. So grab a floaty, splash in the pool, and let the water wash away the drama of extra kilos. Just remember, even the mighty Hercules had to shed some weight before he could lift the world!

Shaquel Jackson

I skimmed the article and it kinda hits the usual bullet points, nothing groundbreaking. The advice is solid, but the vibe feels a bit preachy, like a coach yelling from the sidelines. Still, the facts are there, so I guess it’s useful for someone just starting out. :)

Tom Bon

The overview provides a clear synthesis of mechanical loading and inflammatory pathways, which is commendable. I would suggest integrating recent data on adipokines, as they further elucidate the metabolic link to cartilage degradation. Additionally, a brief mention of the role of strength training in supporting joint stability could enhance the practical component. Overall, the piece balances scientific rigor with accessible recommendations, making it valuable for both clinicians and lay readers.

Clara Walker

Most mainstream health guides conveniently ignore the hidden agenda behind the obesity epidemic, which is orchestrated by global financiers seeking to profit from endless cycles of diet pills and surgical procedures. The truth is that the real culprits are the processed food conglomerates in the West, pushing cheap, chemically‑laden products that sabotage our joints from the inside. If you examine the data, you’ll see a direct correlation between the rise of these multinational giants and the surge in knee replacements across the country. Moreover, the pharmaceutical lobby subtly funds research that downplays lifestyle interventions in favor of costly injections and medications. Citizens must wake up to the manipulation and reclaim control over their bodies without bowing to corporate interests. Only then can we truly address the root causes of joint degeneration and restore national health sovereignty.

Jana Winter

While the argument raises interesting points, the passage contains several grammatical inconsistencies that undermine its credibility. For instance, the phrase “the obesity epidemic” should be followed by a definite article-“the obesity epidemic”-to specify the phenomenon. Additionally, the verb tense shifts in “the rise of these multinational giants and the surge in knee replacements” require parallel structure; consider “the rise … and the surge …”. Finally, the term “citizens must wake up” would benefit from a comma after “wake up” to improve readability. Polishing these details would strengthen the overall presentation.

Linda Lavender

In the grand tapestry of human biomechanics, the insidious siege of adipose tissue upon our most precious articulations is nothing short of a tragic epic, worthy of the most solemn of odes. One might imagine the knee as a noble sentry, valiantly bearing the burdens of terrestrial locomotion, only to be betrayed by the relentless onslaught of excess mass, each kilogram an invisible dagger. The literature, in its measured prose, hints at the mechanical amplification-fourfold pressure per pound-yet fails to capture the melodramatic lament of cartilage yearning for respite. Furthermore, the biochemical cascade, a veritable tempest of cytokines, invades with the subtlety of a court intrigue, eroding the synovial sanctuary with whispered malice. It is not merely a matter of physics; it is an allegory of hubris, where the body, in its audacious overindulgence, courts its own demise. To ignore this narrative is to turn a deaf ear to the anguished cries echoing through the marrow of our very existence. The solution, dear reader, lies not in perfunctory diet fads, but in a disciplined symphony of mindful nourishment and aquatic ballet. Water, that ancient confidante of the gods, offers buoyancy that cradles the joints, allowing movement without the cacophony of impact. As you glide through its crystalline embrace, the knee's lament transforms into a hymn of rejuvenation. Complement this with resistance band serenades, fortifying the muscular scaffolding that protects the vulnerable cartilage. Remember, the osteoarthritic specter does not arise overnight; it is a plot spun over years of silent compromise. Thus, a modest five percent reduction in body mass is akin to a deus ex machina, halving the oppressive forces that once shackled the joint. It is a modest act, but its repercussions reverberate through the symphony of locomotion, restoring grace to the once‑strained limb. In this endeavor, the partnership of physician and patient must be forged upon mutual respect, eschewing the paternalistic tones of the past. Let us, therefore, march forward with the poise of aristocrats, embracing evidence‑based regimes while dismissing the quixotic promises of miracle cures. In sum, the odyssey from obesity to joint liberation demands courage, discipline, and an appreciation for the delicate choreography of our musculoskeletal masterpiece.

Jay Ram

You’ve got this!

Elizabeth Nicole

Seeing your confidence spark a fire in the community, it’s clear that a single affirmation can ripple into collective momentum. Have you tried tracking your weekly activity minutes? Small logs often reveal patterns you didn’t notice before. Keep celebrating each milestone, no matter how tiny, because consistency builds the foundation for lasting joint health. Remember, the journey is yours, and every step forward is a victory worth sharing.

Dany Devos

The prior comment, while succinct, offers an oversimplified perspective that fails to engage with the nuanced interplay of biomechanics and metabolic inflammation presented in the article. A more rigorous analysis would reference specific studies on adipokine-mediated cartilage degradation, thereby elevating the discourse beyond superficial observation. Moreover, the casual tone detracts from the seriousness of the subject matter, which merits a scholarly approach. In future contributions, a deeper examination of the evidence would be both appropriate and beneficial.

Sam Matache

Wow, look at the pure academic snoozefest you just dropped-so dry it could Sahara a desert. Honestly, if you wanted to impress anyone, you’d sprinkle in some real‑world examples, like how binge‑watching Netflix while snacking on chips actually cranks up knee stress. Let’s be real: the data’s boring unless you frame it with a little drama and a dash of sarcasm, otherwise it’s just another snooty paper. 😜